Japan—Mild inflation and rising wages end negative interest rates

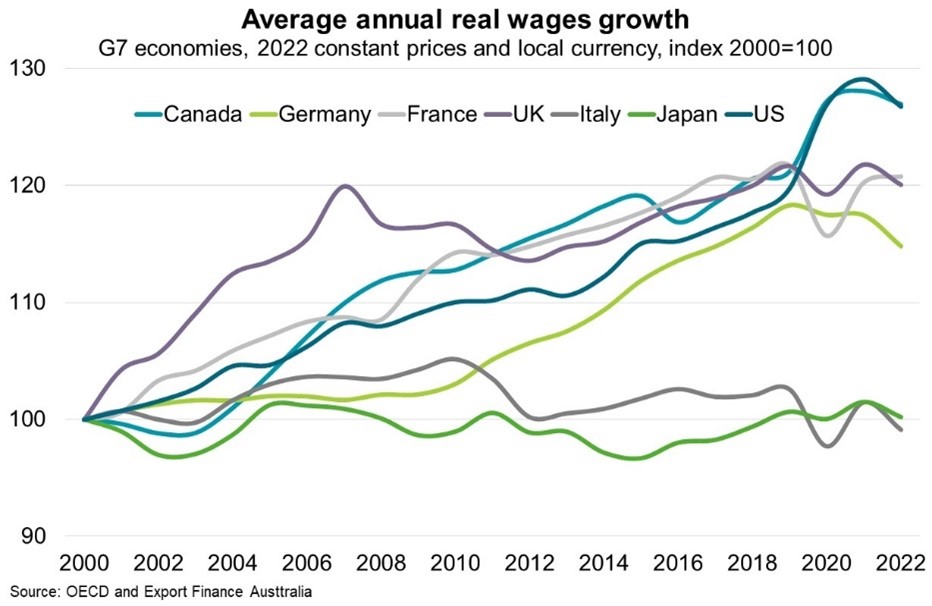

Last month, the Bank of Japan ended negative interest rates, raising borrowing costs for the first time since 2007 in the world’s third biggest economy and Australia’s second largest export market. Since the late 1990s, Japan has been the only advanced economy where inflation, interest rates and wages growth consistently remained near, or below, zero (Chart). Indeed, Japan’s real GDP grew an average of just 0.9% annually between 1990 and 2022, compared to 2.4% in the US over the same period. Reflecting weak economic activity, the Tokyo Stock Exchange only recently recovered to the peak reached in 1989. By contrast, the New York Stock Exchange took just six years to regain its 2007 peak.

However, the twin shocks of COVID-19 and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have prompted two years of inflation. In response to rising prices, Japan’s largest employers recently agreed to increase average wages by 5.3% during annual Shunto pay negotiations, the biggest raise since 1991. Policymakers hope a virtuous cycle of rising prices and wages has begun to emerge.

However, more evidence of rising real wages and shifts in consumption, savings and investment decisions will be required to declare an end to deflation and sustain a series of interest rates hikes. In particular, it remains unclear whether wage increases by Japan’s largest companies will trickle down to SMEs, which employ 70% of workers but have less scope for productivity gains. Further, deep-rooted structural challenges remain. Domestically, this includes government debt and a declining population and workforce. Japan’s economic performance also remains muted; according to a recent Cabinet Office survey, a record 63% of respondents do not feel financially comfortable. Externally, China’s deflationary pressures and muted consumer demand could have ripple effects on Japan’s trade-dependent economy.