2022—Australian exports benefit from sharply higher commodity prices

Global growth slows

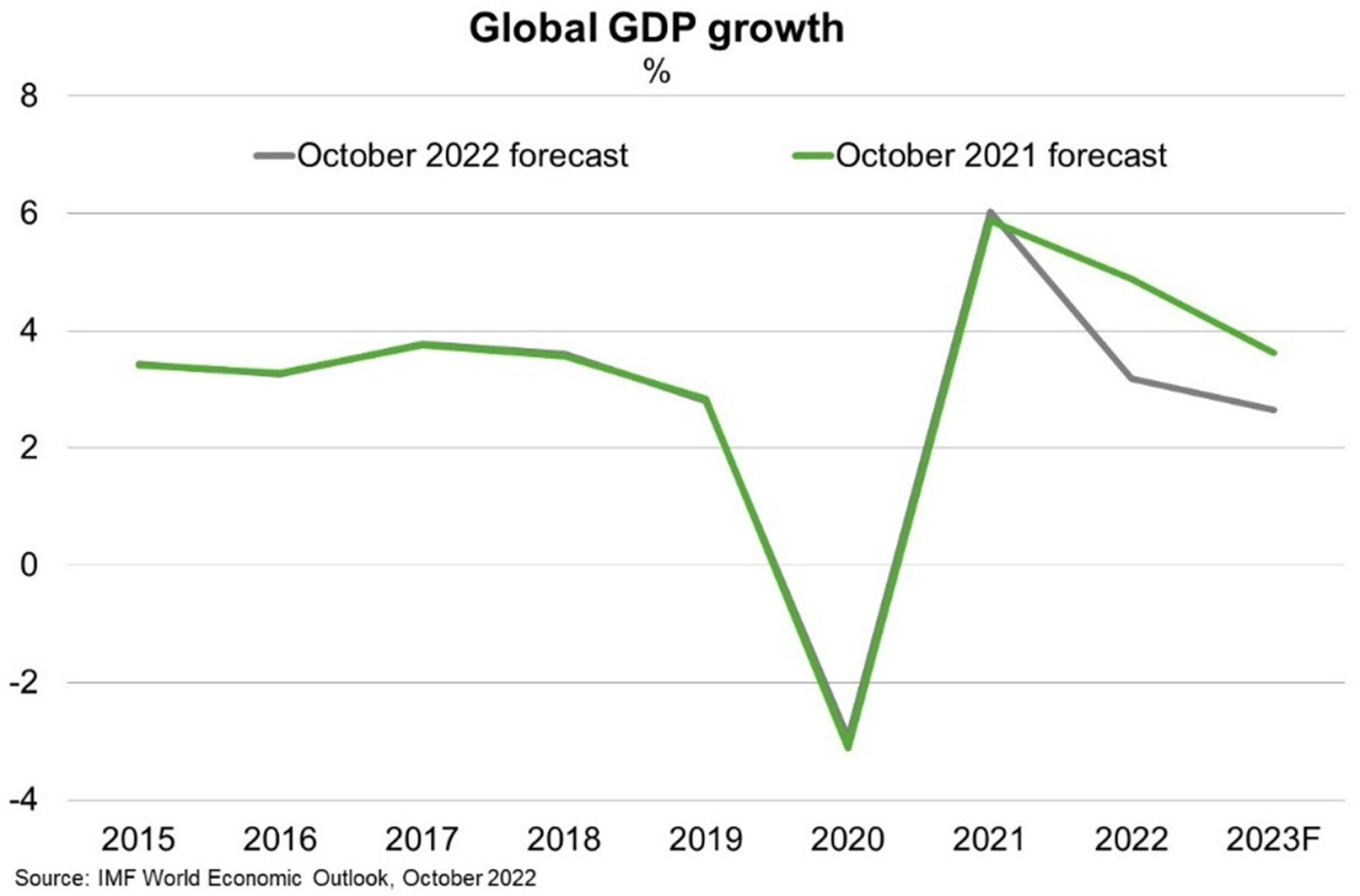

After bouncing back strongly from the COVID-19 pandemic, the global recovery slowed through 2022. The IMF downgraded its economic forecasts again in October, and now expects the world economy to grow just 3.2% in 2022 (Chart). This mostly reflects slowdowns in the world’s largest economies—the US, Europe and China.

Strict COVID-19 policies and property downturn crimps China’s recovery

As the Omicron COVID-19 variant spread earlier this year, higher infections and renewed mobility restrictions worsened labour shortages and disrupted stretched global supply chains, most prominently in China. Strict COVID-19 policies and recurrent mobility restrictions weighed on Chinese consumer confidence, private consumption and manufacturing activity. Although recent easing of some COVID-19 measures will help to improve China’s growth outlook, implementation is likely to be uneven, disruptive and low vaccination levels present risks to public health. China’s property market also rapidly weakened in 2022, exacerbating the slowdown (Chart). Rising financial stress for developers and banks contributed to declining real estate investment, home sales and house prices. Chinese authorities responded by cutting interest rates and ramping up infrastructure spending. But high corporate and local government debt prevented super-sized stimulus measures, as seen in the past. Severe heatwave and drought in Southern China (and heavy rainfalls in the North) added to economic challenges, disrupting China’s water and electricity supply and damaging agricultural production.

Reflecting these challenges, the IMF expects China’s real GDP growth to be 3.2% in 2022, the weakest in more than four decades (excluding the COVID-19 pandemic), and well short of the authorities’ 5.5% target.

War boosts global energy and food prices

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine resulted in supply chain disruptions and soaring global energy prices. Surging import costs contributed to higher inflation and weaker business investment and consumer spending across Europe, particularly in Germany. The war also disrupted global supplies of wheat, corn, barley, and seed oil and pushed food prices higher.

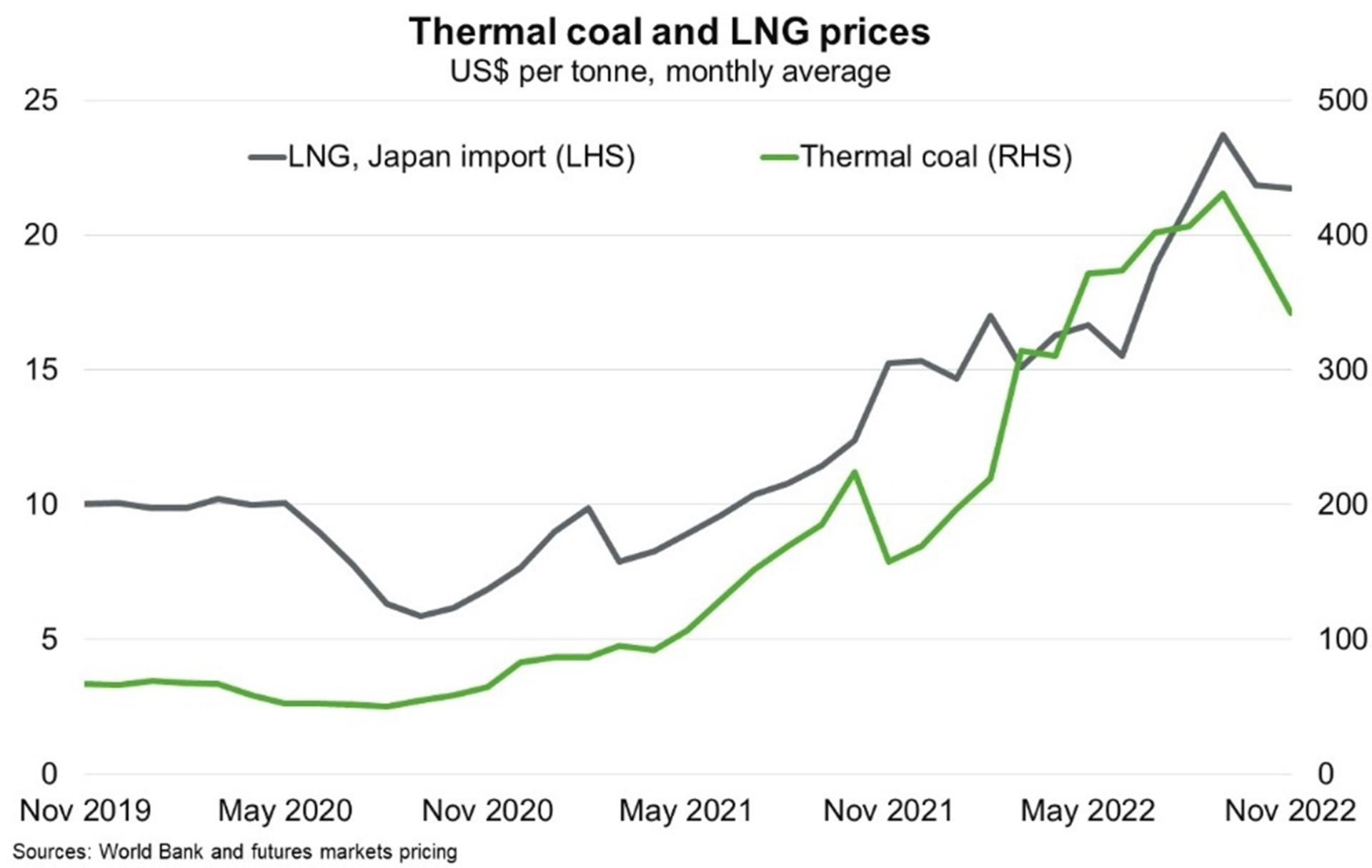

Russia’s continued curtailment of natural gas flows prompted European buyers to strongly increase LNG imports from other countries, leading to a tightening in the global gas market. Gas shortages in some emerging markets prompted switching to other fuels such as coal and oil for power generation. Bans on imports of Russian oil and coal by most advanced Western countries further dented energy supplies. Reflecting higher demand and lower supply, thermal coal prices rose to a record high US$440 per tonne in late-September (and remain high at around US$400 in early December), while LNG prices roughly doubled in 2022 (Chart).

Emerging markets suffered disproportionately from higher global energy and food prices and weaker external demand, prompting social unrest in some countries. Political uncertainty remained a challenge to economic recovery and investment in several emerging markets, including Brazil, Malaysia, Chile, Turkey and Pakistan.

Rising inflation increases import costs and worsens debt distress in emerging markets

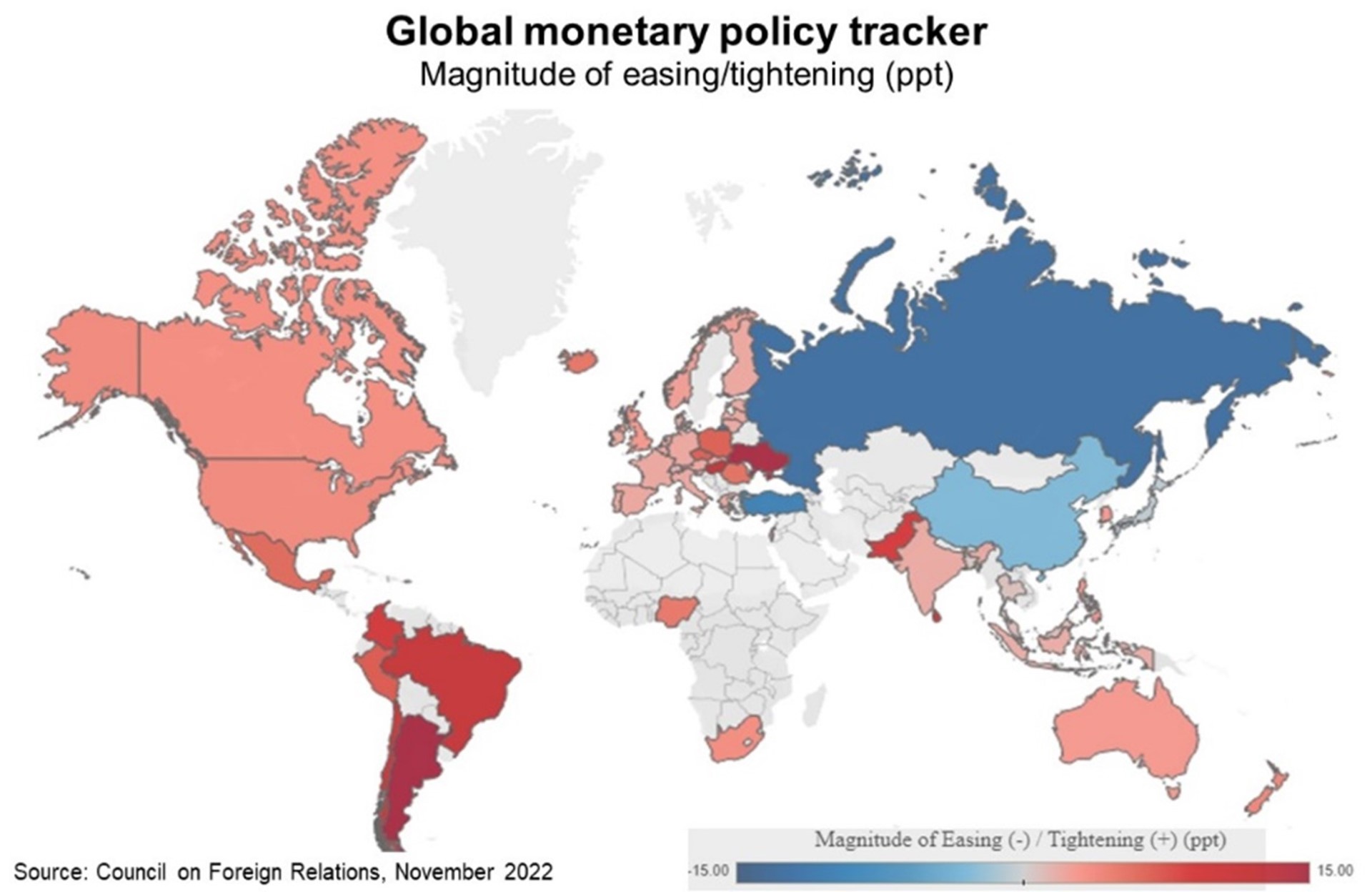

High and persistent inflation this year reflected pandemic-related fiscal and monetary stimulus, labour shortages, and higher global energy and food prices linked to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. This prompted aggressive interest rate hikes from most central banks around the world (Chart). Rising inflation and higher interest rates eroded consumer spending and also contributed to import cost pressures. Rising wages, increasing interest rates and supply disruptions disproportionately hurt small businesses (62% of all Australian exporters) that have less scope to raise prices on global markets and mitigate rising costs.

Tighter financing conditions, including rising interest rates and depreciating currencies, also worsened debt vulnerabilities in emerging markets. In particular, African governments faced significant financing pressures in 2022 as large debt maturities came due.

Supply chain and labour market disruptions persist

Tight labour markets and worker shortages characterised most OECD countries over the past year, including in Australia, proving a headwind to exports. On the supply side, 44% of Australian manufacturers cited ‘labour’ as the single factor most limiting production in the September ACCI–Westpac Survey of Industrial Trends, in line with the series high in 1973. On the demand side, labour market constraints weighed on economic prospects in Australia’s major advanced export markets.

Disruption to semiconductor supplies hit products used in critical sectors such as health, defence and telecommunications and created challenges for manufacturers globally. Shipping contract rates remained high amid elevated fuel prices and ongoing shortages of vessels, though supplier delivery times, order backlogs and queues at ports eased later in the year. Meanwhile, La Niña weather events disrupted global food supplies and further contributed to higher food prices. In response to rising costs, many Australian businesses changed their operations and processes, cut back on investment, sought additional finance or renegotiated payment terms with customers and suppliers.

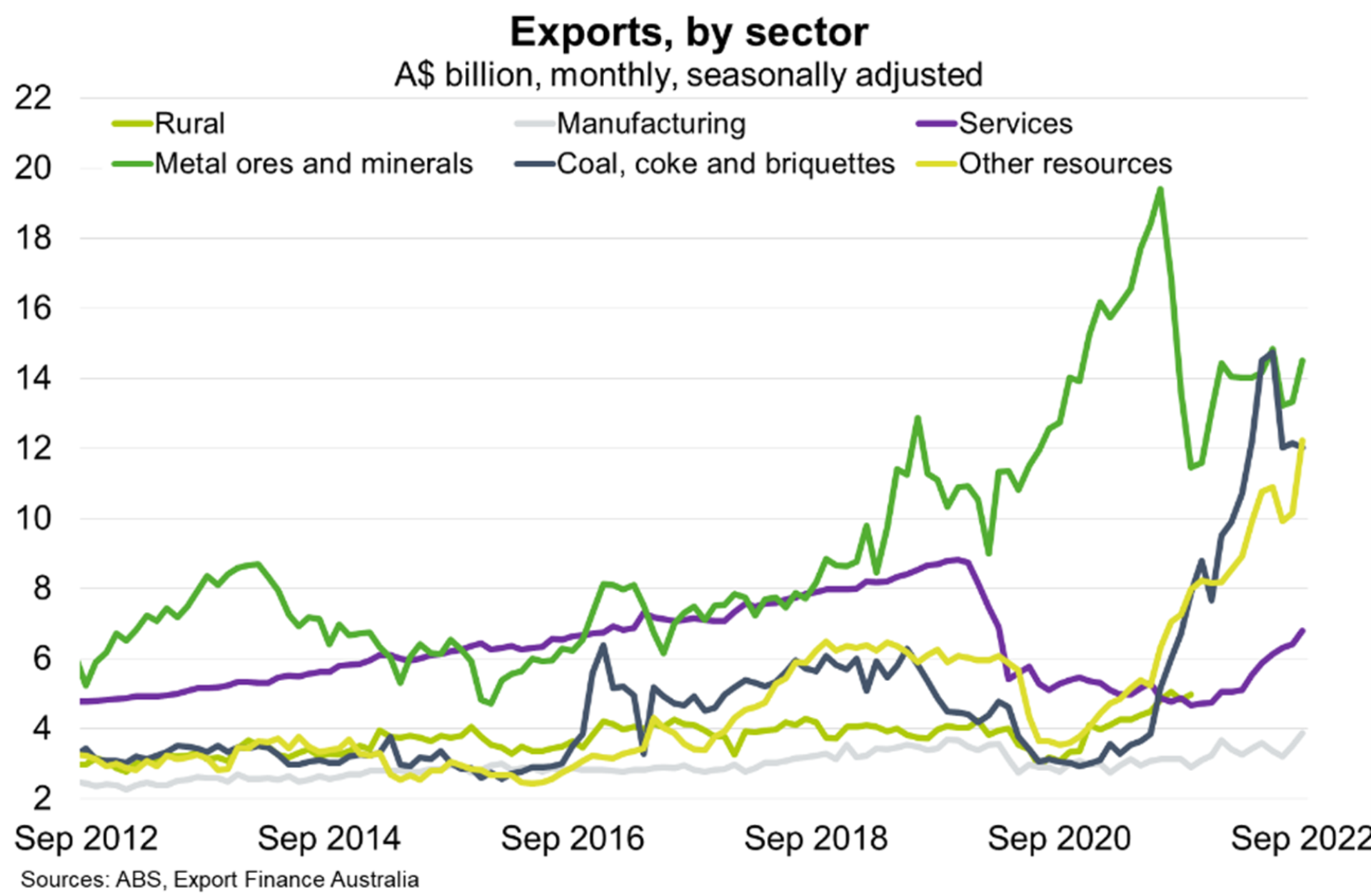

Exports resilient to global issues, benefitting from sharply higher commodity prices

Despite a difficult external backdrop, Australian exporters benefited from sharply higher energy, metals and grains prices (Chart) as Russian and Ukrainian supplies exited the market and Australian dollar weakness against the US dollar. But lower levels of property construction and energy shortages curbed Chinese steel demand and dragged on iron ore prices, which are likely to end 2022 near US$110 per tonne from as high as US$150 earlier this year. Non-resources exporters suffered from supply disruptions, higher transport costs and slowing global demand.

Agriculture benefited from favourable growing conditions and high global prices, lifting crop exports in particular. The combination of high production and prices has seen Australian agricultural exports exceed $5 billion in each month since November 2021. Wheat exports alone have accounted for over $1 billion a month during 2022 (to September). Indeed, many agricultural exporters successfully found new markets in the Middle East and Asia to offset lower exports affected by bilateral trade disruptions to China impediments affecting some products. Beverage exports, including wine, to markets other than China also increased this year.

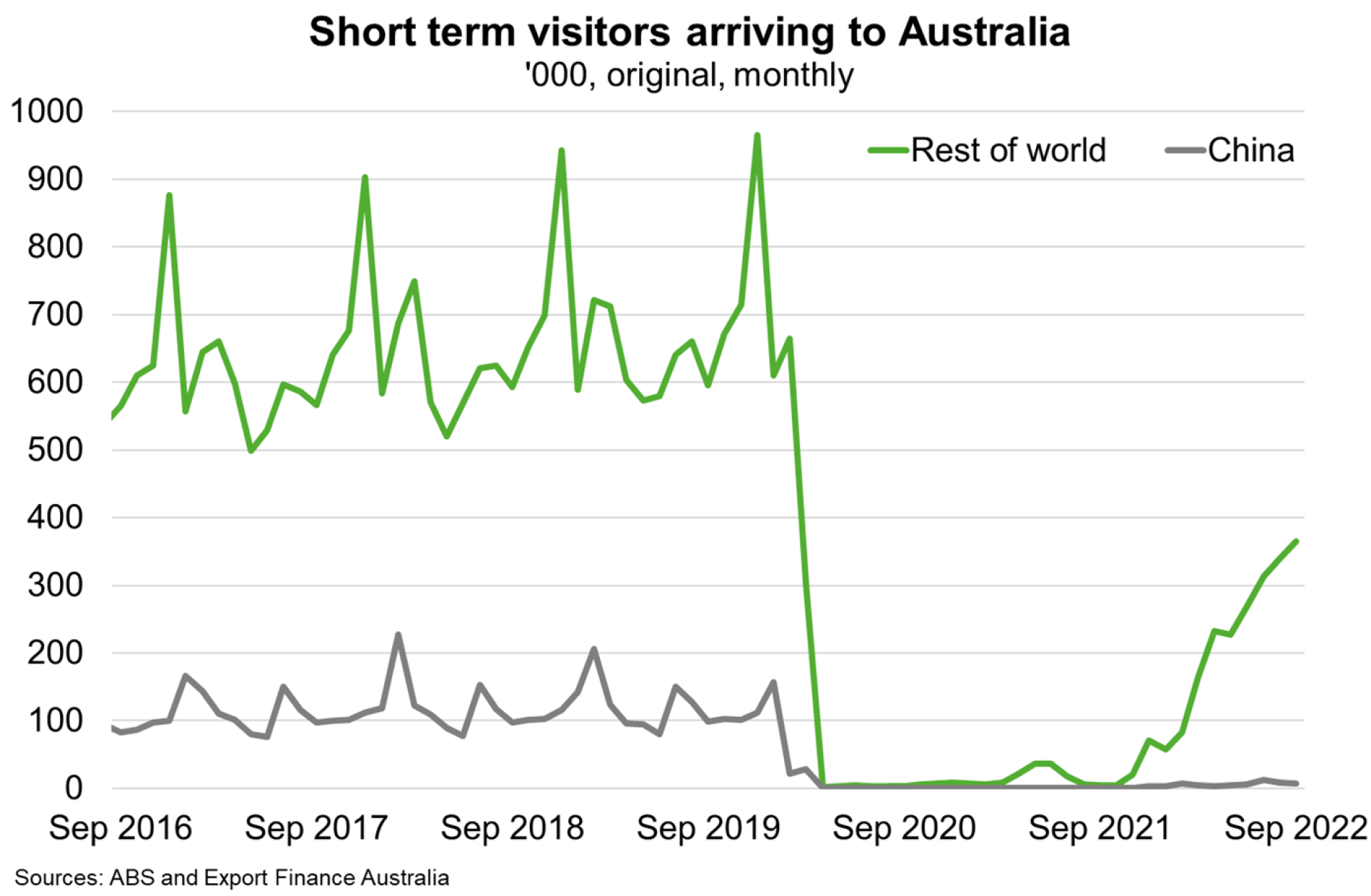

Services exports have risen gradually since Australia reopened its international border in February. Overseas visitor arrivals in September remained about 46% lower than the pre-COVID level in September 2019. Visiting family and friends dominated short-term arrivals, while holiday and business travel is lagging. And departures from Australia have recovered more quickly than arrivals. Travel restrictions in China contributed to the slow recovery in visitor arrivals (Chart); short-term arrivals from China are down more than 90% compared to pre-COVID levels.